“We’ve never thought that you should have to come to work and assume a mask and look like you’re a bunch of little lead soldiers stamped out of a mold. We give people license to be themselves.”

— Herb Kelleher

Most organizations expect people to check their emotions at the door. Others embrace emotions as long as they are positive — they don’t want to hear anything negative.

Regardless of growing praise for how emotions shape people’s performance at work, most organizations don’t manage their emotional culture as intentionally as its intellectual counterpart.

Emotions, both positive and negative, are a fundamental part of who we are — they express our basic intelligence and energy. Herb Kelleher, CEO of Southwest Airlines, taught us that you don’t have to check your heart or your sense of humor at the office door.

Ignoring or suppressing how your people feel is harmful. Successful organizations integrate both their authentic emotional and cognitive cultures. Just like Kelleher did with Southwest Airlines.

The Emotional Arena of Work

For a long time, the dominant perspective has been that emotion is the opposite of rationality.”

— Prof. Myeong-Gu Seo

Emotions lubricate collaboration — they facilitate social interactions.

Stephen Fineman, in his book Understanding Emotion at Work, characterized organizations as “emotional arenas” — their intense emotions divide and bond their members.

Frustration, passion, boredom, envy, fear, and guilt — among others — are deeply woven in the way roles are learned and played. They shape decisions, power plays, engagement, and collaboration.

Sigal Barsade, professor of management at Wharton, warns organizations, “Decades’ worth of research demonstrates the importance of organizational culture, yet most of it has focused on the cognitive component.”

We must integrate both the cognitive culture — the shared intellectual values, norms, artifacts, and assumptions — with the emotional culture — the shared affective values, norms, artifacts, and assumptions that govern which emotions people have and express at work and which ones they silence.

According to Fineman, organizations are often presented as rational enterprises. However, what seems like a comforting picture for the controlling managers, is not necessarily true — we can’t separate our calculative decisions from our intuition.

Numerous studies show that emotions shape intent and behavior in conjunction with cognition. Humans make simultaneous cognitive and emotional appraisals of a situation — they are not handled separately by the brain.

Feelings and emotions lubricate, rather than impair, rationality, according to neuroscientist Antonio Damasio. They help us prioritize, ease dilemmas, and make choices. Chicken or pasta? — studies showed that people with damage in the part of the brain where emotions are generated couldn’t make that simple decision.

As Stephen Fineman wrote, “Rationality is no longer the master process; nor is emotion. They both interpenetrate; they flow together in the same mold.”

Unfortunately, many executives still see soft and hard skills as antagonistic — we must integrate both rationality and emotion rather than idealizing one over the other.

Our Problem With Negative Emotions

Optimism has become almost a cult, according to social psychologist Aaron Sackett — pessimism comes with a deep stigma.

Labeling people creates more issues. When someone is ‘identified’ as either positive or negative, or as emotionally intelligent or not, it divides rather than integrate the emotional culture.

In most organizations, executives quickly learn to cultivate sunny emotions. Norms and research accentuate the benefits of encouraging positivity in the workplace. However, based on my research and consulting, this is an indication of teams that have learned how to manage emotions effective, not that they are always positive.

Sophie von Stumm has a piece of practical advice. The psychologist at Goldsmiths University, London spent many years researching the impact of mood and work. She recommends that, instead of worrying about low mood pulling us down, to focus on good mood as a cognitive performance booster.

Unfortunately, the quest to attract top talent sometimes turns culture into a PR stunt — organizations prioritize projecting a perfect image over honesty.

Authenticity eats a ‘positive’ culture for breakfast.

Both positive and negative emotions exist for a reason. Employees are sensors — they detect both problems and opportunities. Rather than dismissing negative emotions, understand what they are telling you about your leadership, team, or company.

Being positive is accepting reality, not idealizing it— a positive outlook helps us acknowledge and integrate both positive and negative emotions.

In this in-depth MIT article, Christine Pearson explains that, when it comes to managing negative emotions, most executives pressure employees to bottle their emotions. Or hand them off to HR.

According to the leadership professor’s research, most managers simply don’t know how to deal with negative emotions.

Some blame it on their own bosses’ behaviors which force them to silence negative sentiments of their own and those of their team members.

Many executives complain that dealing with negativity drains too much time and energy. Others worry that their intervention could make things worse. Many more report they’ve had no training about handling negative emotions neither effective role models.

Not surprisingly, all respondents could name bosses who missed business opportunities or generated unnecessary costs by mismanaging emotions at work.

It is impossible to block negative emotions from the workplace — no organization is immune to people’s highs and lows. However, most senior executives just want to listen to goods news, not to understand the reality of their teams.

“Our CEO doesn’t want to hear anything negative. Not a word about dissatisfaction.”

Dr. Michael Parke says. “When people are invested in their jobs, they can get upset or frustrated with things, but they should be able to share those emotions, so it doesn’t stymie their work or creativity.”

Research suggests that the inhibition of our feelings shrinks the neurons that cause norepinephrine; it leads to a toxic process in our brain. Negative emotions are a signal — silencing them won’t make problems go away.

Fake it Until You Burn Out

When the customer is king, employees become their servants. Forcing people to suppress their emotions is harmful to both employees and organizations. As Lucy Leonards, occupational therapist, explains, “The continuous regulation of their own emotional expression can result in a reduced sense of self-worth and feeling disconnected from others.”

Much work, especially face-to-face service (such as flight attendants, waitresses or secretaries) involves having to present the ‘right’ emotional appearance to customers.

That’s when Emotional labor kicks in at work. This term coined by sociologist Arlie Hochschild refers to how we regulate our emotions to create “a publicly visible facial and bodily display within the workplace.” This emotional labor sometimes requires ‘feeling good’ about the client too.

When the customer is king, managers don’t care about their employees’ feelings — if something goes wrong, they blame their team, not the customer. The key lies in finding balance — neither your team, not the clients should be king.

We must be aware of emotional dissonance — a negative feeling that develops when a particular emotion conflicts with one’s identity.

There are two specific types of emotional labor. Surface acting is when a person has to fake emotion — a tired flight attendant forces herself to smile and be friendly with a disrespectful passenger. Deep acting is about exhibiting emotions they have worked on feeling — it’s about empathizing and feeling sympathy.

Faking emotions causes stress and burnout. The second approach may be healthier according to Barsade. Those who report regularly having to display emotions at work that conflict with their own feelings are more likely to experience emotional exhaustion.

For example, most Walt Disney World onstage employees engage in surface acting, which, for many of them, leads to emotional exhaustion. To balance this, they turn their backstage time — when they are not dealing with customers — into a place to “talk about anything, rant, and rave about the company.” Employees feel the pressure to be “so happy” on-stage that to release that emotional burden, they turn the back-stage into a “venting area” — they vent their feelings by attacking the organization.

The pressure to be always positive can backfire — being authentic is what matters the most.

Authenticity Has Benefits

Workplaces, where employees feel comfortable expressing their feelings, tend to be more productive, creative and innovative.

That’s the key finding of studies by Myeong-Gu Seo and Michael Parke, professors at the University of Maryland’s School of Business and London School of Business, respectively.

Their research focused on understanding organizational climate — the shared perception that people have of their workplace based on its processes, structure, and culture — and the emotional behaviors they engender. A big factor that determines this feel is ‘employee affect’ — a term that encompasses moods and emotions.

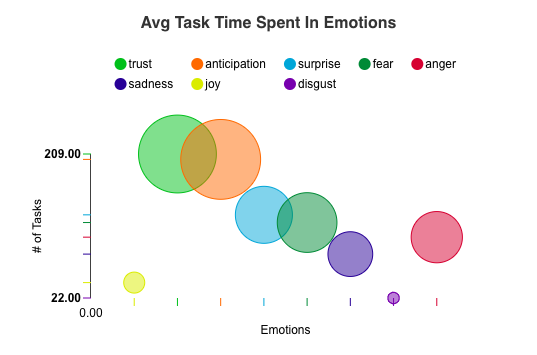

The researchers determined six different mood-based climates — ranging from workplaces that suppress positive, negative or any display of emotion, to those that welcome positive, negative or all authentic emotional experiences and expressions.

“It’s true that sometimes emotions screw up,” says Seo, “but emotions are something to utilize, not to suppress or minimize, at work. If you look at Google, for example, and other good organizations out there, they actually foster and utilize emotion rather than killing it.”

Organizations that encourage people to be open and honest about their emotions perform better at:

- Collaboration — establishing strong ties with colleagues

- Productivity — the amount of work a team accomplishes when given a certain level of resources

- Creativity — the number of new and helpful ideas a team generates

- Reliability — the ability to avoid making mistakes or errors, particularly in high-pressure situations

Organizations that tackle employees’ moods and feelings outperform those that ignore emotions or force people to suppress negative ones.

The Power of Your Emotional Culture

Emotions are powerful but are not the solution — organizations must balance both their cognitive and emotional culture. Here are some ways to leverage the power of emotion I recommend based on my research and consulting.

Move from fear to fearless:

If people are afraid of speaking up, not only they will filter their emotions but keep their best ideas to themselves. Psychological safety is essential to encourage people to take interpersonal risks and create a “fearless organization.”

Just listen:

Ask how people feel — be quick to listen and slow to advise. “Listening meetings” are a powerful tool to hear what’s going on with your team directly. Dave Spence helped recover a mill after a months-long strike by simply “What do you want to talk about?” and then waited and just listened.

Mindset check-in:

Creating a regular space — in recurring weekly meetings, for example — to let people share “What’s got your attention?” not only increases awareness of how people are feeling but helps people remove distractions and drive more focused meetings, as I explain here.

Negative emotions are a signal:

Instead of suppressing or silencing them, listen to what negative emotions are telling you? Is a particular individual going through a rough time or are they a symptom of something that’s affecting your team? For example, Change wears people out — what looks like resistance could be exhaustion.

Be yourself; allow people to be themselves:

Don’t expect people to share their emotions if you don’t show yours first. Role model being human and vulnerable — leaders must balance their cognitive and emotional sides.

Avoid labeling people:

Emotions and moods are fluid. Labeling people as negative or not emotionally intelligent is easy. However, sometimes, those who are considered “problematic” are just playing a role on behalf of the team — they address what everyone is thinking, but no one is saying, as I wrote here.

Beware with blind spots:

Playing the positive role all the time is exhausting — even the most optimistic people suffer from burnout. Seeing only the bright side not only makes them blind to their own kryptonite but can drain their energy. Everyone needs a moment to release their negative emotions.

Monitor team mood:

Many companies, like United Way, use apps or buttons to track individual emotions. However, focusing on the collective mood is more important. When someone is going through a rough patch if others are supporting or balancing negative emotions, the overall group won’t suffer. Whatever tool you use, without psychological safety, don’t expect people to be honest.

Give people a break:

Allow people to take a break from high levels of emotional regulation and acknowledge their true feelings. Organizations that let people take a break behind the scenes tend to fare better under pressure.

About the Author

Gustavo Razzetti helps organizations create positive change. He helps leaders and their teams become the best version of themselves by turning change into a positive experience, not a painful one. Gustavo is a change leadership speaker, consultant, and the author of “Stretch for Change” and “Stretch Your Mind.”

Join a community of over 35,000 change agents. Sign up for Insights for Change Agents— a weekly letter with practical advice, tools, and articles to help you drive positive change.

This post was originally published on Medium.